Multicultural Connections: Discovery Trail

WA Shipwrecks Museum

Walyalup/Fremantle is famed for its multicultural heart, built on the contributions of its Traditional Owners and Immigrant inhabitants. But its multicultural beginnings started long ago, with connections to cultures from all over the world.

Explore the WA Shipwrecks Museum to discover how exploration, trade, and settlement have connected Western Australia to the world throughout history.

How to use this trail:

- Find the locations pictured at each stop below to follow the trail.

- Select as many or as few stops as you like to explore the topic.

Start outside the front of the museum...

Stop 1

Manjaree

(Nyoongar country)

The WA Shipwrecks Museum is located at Manjaree, this area of Walyalup/Fremantle near Bathers Beach. Manjaree has been an important place of trade, meeting, culture and ceremony for Aboriginal people for thousands of years. The Whadjuk Nyoongar people of this region would gather to exchange knowledge and items, to hunt and fish, and for spiritual and social connection.

Today people still meet at this same place, for many of the same reasons. The Whadjuk Nyoongar community continue to share their knowledge and connection to country to all who live and visit Walyalup/Fremantle.

Find the line of bricks outside the entry:

This line of bricks extends through parts of Walyalup/Fremantle, and shows where the original shoreline used to be before European settlement. Over time, the landscape has changed as people reclaimed land from the sea.

The animals etched in the brick are the sea life that Whadjuk Nyoongar people had a deep knowledge of.

What sea creatures can you find?

(Optional Extra - To learn more about Manjaree, you can cross the railway tracks and follow the beachside pathway. Read the signage along the way and explore the plants and environment that make up this significant area.)

Did you know…that different native Australian plants traditionally provided food, medicine, and shelter for Nyoongar people? This knowledge has been shared and held over many generations, and today we still benefit from the properties of these plants.

Enter the Shipwrecks Museum, and head towards to the gift shop to find the following image on the wall...

Stop 2

Early Indonesian contact

(Connecting Australia - Indonesia)

The history of Western Australia’s multicultural connections stretch far beyond the Walyalup/Fremantle area.

Pictured is Worana/Worrorra man, Tjangoli (Samson), standing on a mangrove log raft. This image was captured in 1917 in Camden Sound in the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

Aboriginal people in Northern Australia had contact with other cultures for hundreds of years, with the arrival of Indonesian fishermen from Macassar in Sulawesi (Indonesia). From the 1600s, fleets of these fishermen came to Australia to gather trepang (also known as a sea cucumber), which was used in the preparation of Chinese food and medicine.

The Maccassans traded with the Aboriginal people, exchanging items like tools, food, and other resources in return for locally sourced materials and goods.

These connections made Aboriginal people part of an international trade network, well before European settlement across Australia.

In a map App (on your phone or tablet), compare the locations of Indonesia and Northern Australia. How challenging do you think a journey between these locations might have been in the 1600s?

Have you or someone you know been to Indonesia? How did you/they get there?

Want to know more?

Learn more about mangrove log rafts here.

Enter the Hartog to de Vlamingh Gallery, and find the painting pictured below.

Stop 3

Dutch Exploration

(Connecting Australia - The Netherlands)

Western Australia has a long-shared history with the Netherlands. The powerful Dutch East India Company (VOC) established a trade network throughout Asia seeking rare spices and exotic textiles, as well as forging new markets for their goods.

Their trade routes took them along the Western Australian coast, where they explored and made observations of the landscapes, plants, animals and people they encountered. They also mapped the coastlines, and were sometimes shipwrecked on our shores.

This painting shows an East Indies trade expedition returning to Amsterdam. These expeditions were long, dangerous and expensive, so a successful return was a reason to celebrate.

Find the spices nearby:

Spices were used:

• to preserve food

• to improve the flavour of food

• as important ingredients in medicines.

These spices didn’t grow in Europe, so they were very expensive items to buy - only the rich could afford them.

Today, we are fortunate that they are more affordable. You may have seen some spices for sale in your local supermarket.

Can you find the following spices in the cabinet?

- Pepper

- Cloves

- Cinnamon

- Tea and coffee

How many of the spices on display do you have in your kitchen pantry at home? Do you have others?

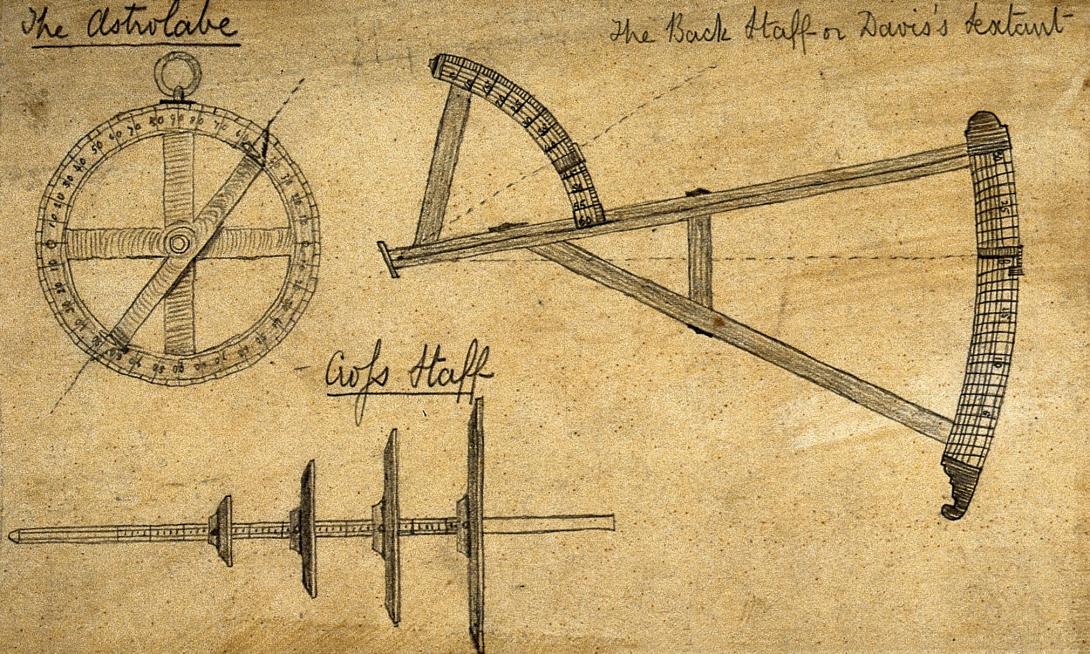

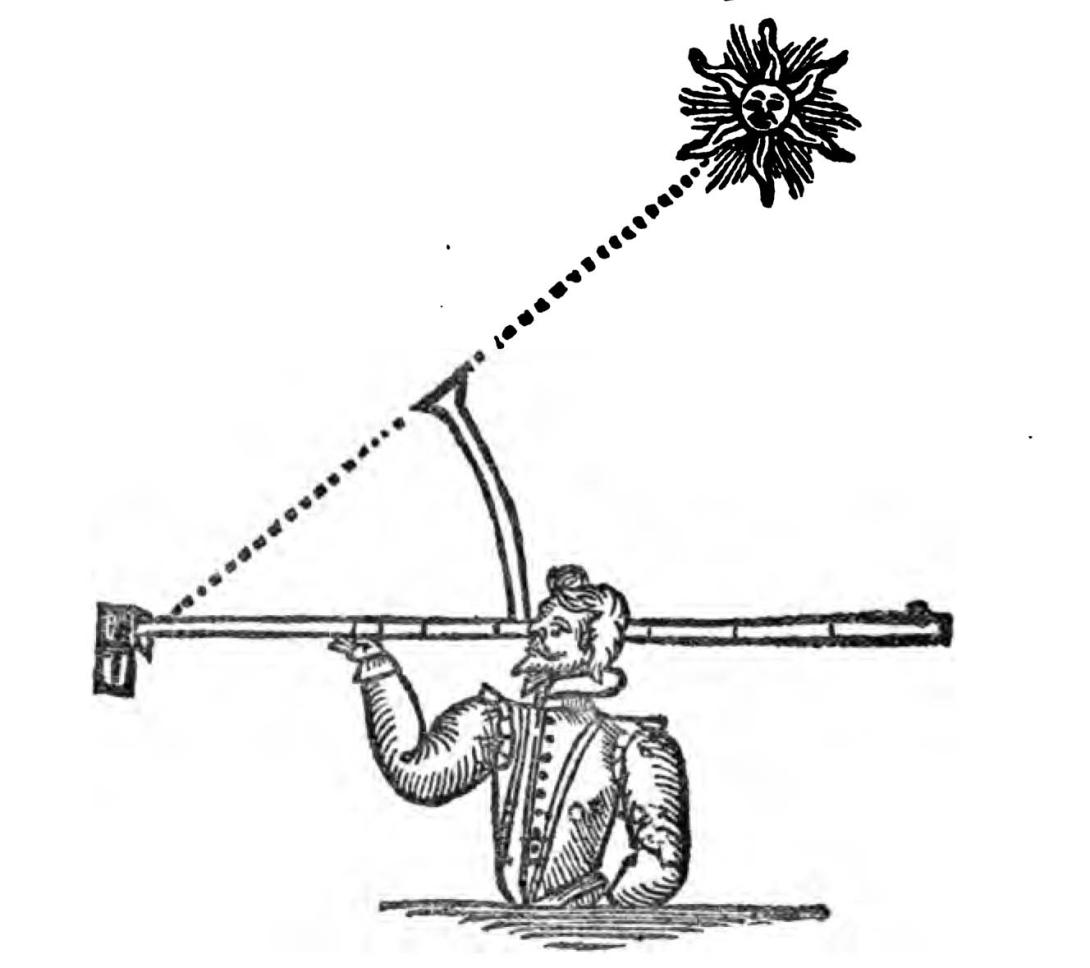

Move further into the gallery until you find the astrolabe pictured below.

Stop 4

Navigation - Opening up the world!

(Connecting Australia - The Netherlands – Indonesia)

The journeys of Dutch ships along the Western Australian coast to the ‘Spice Islands’ links Australia with both the Netherlands and Indonesia throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Navigational tools like this astrolabe made such journeys possible, opening up the world to exploration, trade and the exchange of ideas and culture. However, they were not always accurate instruments, which led to many ships sailing too close to the Western Australian coast where they were wrecked. This astrolabe came from the Dutch East Indiaman Gilt Dragon, wrecked near Ledge Point in 1656.

Look around the gallery to find some other navigational tools from the past.

How do we explore our world today?

How would you find your way home if you got lost today?

Want to know more?

Learn more about astrolabes here.

Learn more about backstaffs here.

Keep sailing ahead until you find the display pictured next!

Stop 5

Comparing Cultures

(Connecting Australia - The Netherlands)

In 1616, Dutch navigator Dirk Hartog became the first recorded European to land on the Western Australian coast at what is now Shark Bay. Since then, many more Dutch ships followed, visiting the WA coastline to map, explore and discover more about what they called the ‘Great Southland’, and later ‘New Holland’. They hoped to find wealth, fertile lands and trade possibilities, but instead found very unfamiliar land, vegetation, people and animals.

On display here is a small selection of weapons used by the Dutch in the 1600s. Items like this may have been brought ashore when their expedition parties explored the area.

In contrast, look at some of the weapons and tools that the Traditional Owners used.

What are the similarities and differences between the Dutch and Aboriginal tools and weapons on display?

Look at the image of people behind the weapons display:

How different do you think the lives and cultures of the Dutch Explorers and the Australian Aboriginal people were in the 1600s?

Did you know…the Dutch did not think that New Holland (Australia) was suitable to colonise. They were looking for things they could trade, and saw no spices, precious metals, or cities to trade with. Although they recorded a lot of their observations, they did not take time to learn more about the abundance of natural resources that the Aboriginal people knew so well, and they simply left the coastline in search of other riches.

Turn right from this display, and walk under two arches to find the ‘plate’ in the far corner of this gallery.

Stop 6

Cultural calling card – Hartog and De Vlamingh plates

(Connecting Australia - The Netherlands - France)

In 1616, Dirk Hartog landed on an island off the Western Australian coast that now bears his name. To mark his visit, he left his ‘calling card’ - an engraved pewter dish, nailed to a timber post. (You can see a replica of the Hartog Plate in front of you. The original is now held at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam).

Later expeditions took great interest in this ‘plate’:

1697 - Willem de Vlamingh’s Dutch expedition found Hartog’s 1616 plate. They took it back to the Netherlands, but replaced it with a new one, engraved with Hartog’s original words as well as their own.

1801 - Nicolas Baudin’s French expedition found de Vlamingh’s plate fallen from its post, and reattached it to a new post.

1818 - Louis de Freycinet’s French expedition removed de Vlamingh’s plate and took it back to France.

1947 - The French government returned the de Vlamingh plate to Australia in recognition of its historical significance.

Find the real de Vlamingh plate nearby:

Why do you think the Hartog and de Vlamingh plates are so historically significant?

If you were visiting a new, unknown country, what would you LEAVE behind as a souvenir to commemorate your visit? What kind of souvenir would you TAKE from such a visit?

Did you know… European seafarers often left materials or messages at places they visited? The Dutch used plates and boards, the French buried coins and bottles, and the British (including James Cook), marked their visits on trees or rocks.

Want to know more?

Learn more about de Vlamingh’s plate here.

Learn more about the posts here.

Find out more about Dirk Hartog Island and its international connections here.

Look nearby for a furry friend…

Stop 7

Multicultural mascot

(Connecting Australia - The Netherlands - France)

Western Australia’s Black Swan and Quokka became multicultural mascots when first encountered by Europeans. Once 'discovered', European explorers shared their knowledge and introduced Western Australia to their world.

When Willem de Vlamingh’s expedition landed on Rottnest Island (Wadjemup) in 1696, they discovered its resident quokkas. He thought they were ‘a kind of rat as big as a common cat’, so named the island Rottenest or ‘Rat’s Nest’ after them.

Compare the quokka and the rat on display. Do you think they look similar?

Just for fun … take a selfie with the quokka!

Find this nearby display of the swan:

When de Vlamingh’s party reached the mainland, they were surprised to discover the existence of black swans. They named the river after them - ‘Swarte Swaene-Drift’ (Black Swan River) or ‘Zwaanenrivier’. The Aboriginal name for the Swan River is Derbarl Yerrigan.

Much later, on Nicolas Baudin’s French maritime expedition (1800-1804), an assortment of Australian plants and animals were collected and returned to France for scientific study.

Black swans, kangaroos and emus were brought to live in an exotic private zoo at the palace of Emperor Napoléon Bonaparte’s wife, Joséphine.

Why do you think the Dutch were surprised to find that Western Australia’s swans were black?

Why are live animals still collected and displayed in other countries today? Is this practice helpful or harmful?

Fun Fact:

Empress Joséphine Bonaparte developed such a love for the black swans that she included their design (as well as Australian plants and flowers) into her wallpapers, silks, and even her carved four poster bed.

Enter the Xantho gallery next door.

Stop 8

Xantho – Steaming ahead

(Connecting Australia – Scotland – Singapore – the Philippines – Timor – Malaysia – Indonesia)

The SS Xantho was Western Australia’s first coastal steamship. It was purchased in Scotland by businessman Charles Broadhurst in 1871 to help establish his pastoral (grazing) and pearling industries in the North West of the state.

Xantho linked Australia with many countries and cultures during its use:

- It travelled between Fremantle, Batavia (now Jakarta), Geraldton and Broadhurst's pearling camps in the North West.

- Broadhurst’s pearling divers (referred to as ‘Malays’) came from Singapore, the Philippines, Timor, and present-day Malaysia and Indonesia.

- Xantho also transported a number of Aboriginal men from the Aboriginal prison at Rottnest Island back to their homes near Cossack and Roebourne.

Xantho, and other steamships that came to WA, are an important part of Western Australia’s multicultural past. They connected Western Australia to the world, and provided important trade and communication links, brought new migrants to the state and carried mail, passengers and cargo.

Explore some of the other steam ships in the gallery – which one did you find the most interesting and why?

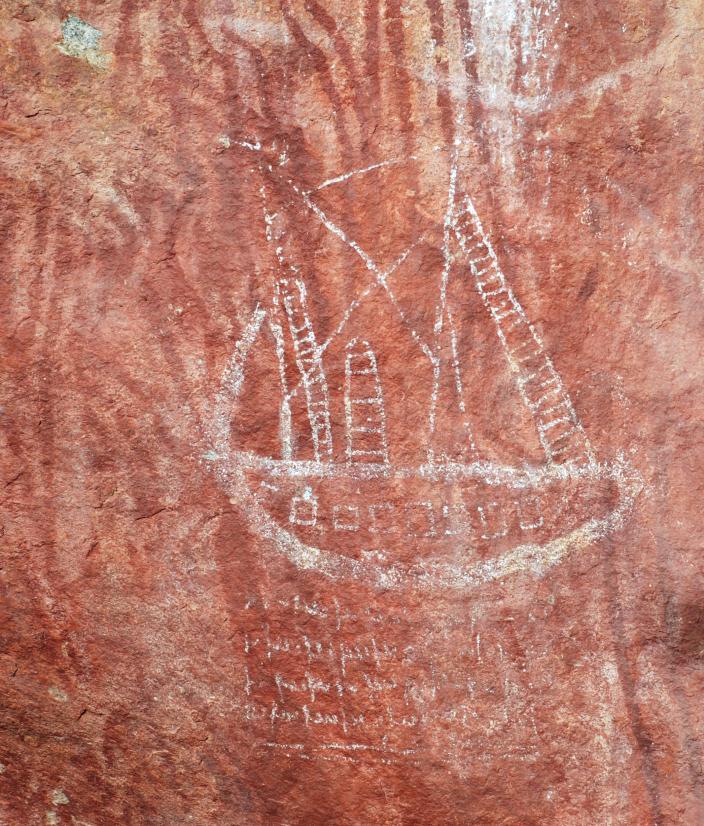

Find this image at the far end of the gallery:

This rock art features a European-style ship, possibly the SS Xantho. It is located at Walghana (Walga Rock), 250km inland and far from the coast.

Not all steamship stories are positive. Read the information panels near this image to learn how many Aboriginal and ‘Malay’ workers in the pearling and pastoral industries were mistreated.

Who might have created this artwork and why?

Find this display nearby:

Where are these objects from?

Which cultures do they connect?

Want to know more?

Learn more about Xantho here and here.

Learn more about the Broadhurst family and their contributions to the development of Western Australia here.

Move further through this gallery and exit opposite the Xantho engine display. Find the model ship in the hallway…

Stop 9

William Dampier

(Connecting Australia – England)

This model ship is of the Roebuck, on which William Dampier (the famous pirate, explorer, natural scientist, hydrographer, and author) sailed. He was among the first Englishmen to set foot in Australia (then known as New Holland) in 1688 (near present day Broome). He later returned in 1699 (in the Roebuck), and spent three months being the first English person to chart parts of the North West coastline, and the first European explorer to describe, record and collect Australian plants and animals.

William Dampier wrote best-selling books about his travels, sharing his experiences and discoveries of Western Australia with the world.

What might Dampier’s readers at the time have thought of his observations of Western Australia?

How do we find out information about other countries and cultures today?

Just for fun…Look closely at the model ship – how many different figures and animals can you find carved in it?

Move towards the foyer and into the next gallery. Find the James Matthews display pictured below.

Stop 10

Colonial Western Australia

(Connecting Australia – England)

The Swan River Colony was established by the British in 1829. The new colony took a long time to develop and was very remote, so it relied on lots of imported food, drink and goods to supply everyone. The settlers did not understand the local environment or the resources it could have provided.

Take a look at some of the items on display recovered from the shipwrecked James Matthews. When the ship sank in 1841, it was carrying much-needed supplies from England—food and stores that colonists had been eagerly awaiting. Its loss would have been deeply felt across the settlement.

Find 3 items in the display that you might have at home. Which of these items would you find it hardest to live without?

What imports and exports do Western Australians rely on today?

Have you ever experienced a delay in the delivery of something from overseas? How did that make you feel?

Want to know more?

Learn more about the James Matthews:

Delivery Time? About 100 Years or So

Patrick Baker: Exploring James Matthews Video

Head towards the entry of the Museum to find the next stop.

Stop 11

International Trade

(Connecting Australia – The World)

In the Swan River Colony, access to fresh food was not always possible, and the diet could be repetitive and boring. Until the end of the nineteenth century, the Colony relied on imported food and drink brought over by British ships to supplement their limited local supplies. These items came from Britain and beyond, and trade with other countries grew as the years went by.

Spotto!

Locate the containers (pictured below) that were found on ships wrecked during their journey from Britain to the Swan River Colony. Then answer the following:

What countries or places did they come from?

What did the bottles contain?

Do any of the bottles on display still have their original contents?

What do you think it would taste like after all this time?

Go into the Batavia gallery.

Stop 12

Batavia

(The Netherlands – Indonesia - Australia)

The wreck of the Batavia is another BIG example of Western Australia’s connection to the Netherlands and Indonesia. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) trading ship Batavia was sailing to the Dutch settlement of Batavia in the East Indies (now Jakarta, Indonesia), loaded with goods and silver for trade. The Dutch colony of Batavia was the centre of the spice trade for the VOC.

Batavia was shipwrecked on the Western Australian coast on this voyage in 1629. (The epic story of this shipwreck and the resulting survival drama is told in this gallery!) In addition to 12 chests of silver coins and approximately 340 people, Batavia carried a cargo of 137 sandstone blocks.

After the Batavia wreck was discovered in 1963, archaeologists retrieved and fitted the sandstone pieces together like a giant jigsaw, revealing a magnificent portico. (The one you see here is a replica – the original can be seen at the Museum of Geraldton).

But why was there a portico on board the ship?

Find this image nearby and look for some clues…

Answer: A journal from the time reveals a sketch of Batavia Castle’s Seagate missing its gateway – because it lay shipwrecked on the bottom of the ocean instead!

Fun fact:

Not only does this portico link Western Australia to the Netherlands AND Indonesia, but analysis of the stone shows that it was quarried in Germany!

Want to know more?

Learn more about the Portico here and here.

Continue through the gallery and make your way up the small staircase, across the upstairs Batavia Viewing Deck, and into the Dutch Shipwrecks Gallery.

Stop 13

Beardman Jugs

(Connecting Australia – Netherlands – Germany - Belgium)

This style of stoneware container is called a Beardman Jug, and many are found on the Dutch wrecks off the WA coast. They originated in parts of Germany and Belgium, and often contained wine, beer, vinegar or other liquids. They were a popular trade item with China and Japan.

How do you think Beardman Jugs got their name?

Find your favourite face on the Beardman Jugs.

Find the wooden post pictured next nearby (hint: line up the picture below to match the gallery background).

Stop 14

Convict Tales

(Connecting Australia – Great Britain)

Look closely at this beam - can you find some arrows and letters?

This symbol is the Broad Arrow, and it was stamped onto objects and property owned by the British government. You may have seen it on pictures of convict uniforms. The WA Shipwrecks Museum was built by convicts in the 1850s and used as a Commissariat, or warehouse for government supplies, both in colonial times and later. Some of the timber posts in this room are stamped with B^O (‘Board of Ordnance’) or W^D (‘War Department’), which reflects the government departments that operated here.

In its time, this building has stored food and supplies for the colony, timber for export, fertiliser, cotton, and wire netting for rabbit-proof fences.

Almost 10,000 convicts were transported from Britain to Western Australia between 1850 and 1868 and they made significant contributions to the development of the State. They constructed roads, bridges and public buildings, provided labour for many industries, and added to the growth of its diverse population.

Want to know more?

Learn more about the broad arrow here.

Learn more about convict uniforms here.

Save for later…when you leave the Museum today, be sure to take a last look at the windows outside the front entry. Can you find the broad arrow symbol on the window bars?

Find this map in the corner of the gallery…

Stop 15

Where on Earth?

(Connecting Australia – The World)

This is a copy of a world map first published by Pieter van den Keere in the early 1600s. At this time, not much of what is now known as Australia had been mapped. The Dutch first encountered ‘The Great South Land’ or Terra Australis in 1606, and it would take until 1803 for British explorer Matthew Flinders to circumnavigate and accurately map the whole country. He gave the country the name ‘Australia’.

Can you find Australia on this map? Why do you think this is so?

What other countries can you identify?

Find the cabinet of coins at the other end of the gallery…

Stop 16

Cultural currency

(Connecting Australia – The World)

Shipwreck artefacts highlight the presence of visitors to the WA coast. On board the ships featured in this museum were vast amounts of silver coins used for purchasing products such as spices, silk, ceramics and other treasures. These coins included reales from Spain, daalders from the Netherlands, and talers from Germany.

Look closely at the coins in the cabinet and consider:

• What images, words or numbers can you find?

• What common features do they share?

• How can you tell where they come from?

• What can they tell us about the trade networks at the time?

With today’s international trade, are coins still used? Why or why not?

Have you or someone you know travelled overseas before? What currency did that county use, and did you save some of the coins?

Want to know more?

Learn more about coins here.

We’ve come to the end of our journey….

Stop 17

Conclusion - Still Connected

Just as early visitors arrived by sea on journeys of discovery, trade, and settlement, Western Australia remains deeply connected to cultures across the globe through trade, tourism, and immigration.

Fremantle serves as a vital gateway to the state and is a hub for trade and shipping. International vessels laden with containers for import and export arrive daily, while cruise ships bring tourists to its shores. People from all corners of the world have made Western Australia their home, enriching the region with their diverse cultures, traditions, and cuisines.

Western Australia proudly celebrates its multicultural connections—past, present, and future.

Thank you for exploring the WA Shipwrecks Museum today!

WA Shipwrecks Museum, Fremantle

Credit: WA Museum